This is part of a series about meaningful side projects: read the first post here. It’s aimed largely at those designing digital products but may be relevant for anyone creating user-facing stuff — for example film-makers, writers, fine artists, photographers etc. as well as designers.

One challenge that small companies face, but actually has relevance for anyone building a product or service, is how to get to the right answer fast. Being ‘agile’ is seen as pretty important at the moment, but it’s pretty much impossible to get it right first time.

So when starting a major project, whether you’re a company or an individual creator you want to make sure you’re getting to the most meaningful possible version of what you’re doing in as short a time as possible. It just makes sense.

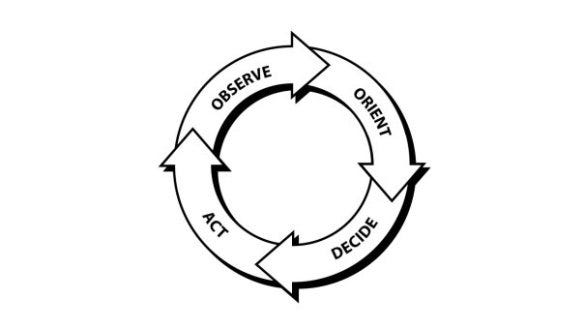

Enter the O.O.D.A. loop.

The ‘O.O.D.A. loop’ shows an effective way of moving quickly and getting to the *right *answer.

The ‘O.O.D.A. loop’ shows an effective way of moving quickly and getting to the *right *answer.

‘In order to win, we should operate at a faster tempo or rhythm than our adversaries … or, better yet, get inside [the] adversary’s O.O.D.A. time cycle or loop.’

The brainchild of military strategist John Boyd, The OODA loop was originally devised to explain the outcomes of dogfights — how could a slower fighter jet with lower capabilities be able to defeat a more technically advanced machine? The answer lay in the pilots ability to more quickly percieve and react to his surroundings — to get his O.O.D.A. loop to be shorter than his opponents (one answer lying in a wider range of vision from his cockpit).

However this O.O.D.A. loop provides a nice way to explain the importance of a short ‘sprint’ or release cycle when creating ‘products’* for people. The quicker you can learn, the quicker you can improve and get ahead.

So how do we apply this methodology to our everyday work?

Rather than cracking open your design tool of choice on day one of a project, start by asking questions and observing behaviour (Observe). Use your learnings (Orient) to build a prototype (Decide) in as short a time as possible, throw it out there (Act) and watch your user again.

The idea is that the faster your ‘O.O.D.A.’ loop is, the quicker you’ll get to a useful and usable product. So if perfecting the bevel on your button doesn’t contribute to that speed of learning, why are you doing it?

Observe: Go to the people who you think might be interested in your idea and check to make sure. Think about how you want to frame your idea to get honest feedback — the last thing you want at this stage is a sycophant telling you the sun shines out of your idea’s arse, only to find out in 6 months that they hated it all along.

Orient: This is a hard one, not just because you need to master an analytics tool of some sort but also know what it is you’re measuring. Measure the wrong thing and you can be left with some assumptions that are just plain wrong. (For example check out the dangers with mixing up causation and correlation). If you don’t have any users, you’ll have to rely on qualitative tests (with individual users or friends) — just be aware that each only provides one data point so may not be statistically significant.

Decide: Based on your learnings revisit your designs and make improvements. The best improvements are small ones that you can test individually — change everything and you won’t know which change was effective.

Act: Release your improved version to your users. They’re getting real value quickly rather than waiting for a future ‘silver bullet’ release and you’re able to learn again.

I’m aware I keep saying product, but this should apply to anything which could involve an iterative process, for example film or music.

Read my first post about side projects here

This article was originally posted on my medium blog